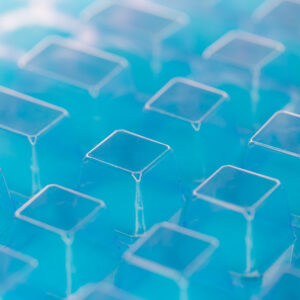

PLA for Drug Delivery Devices

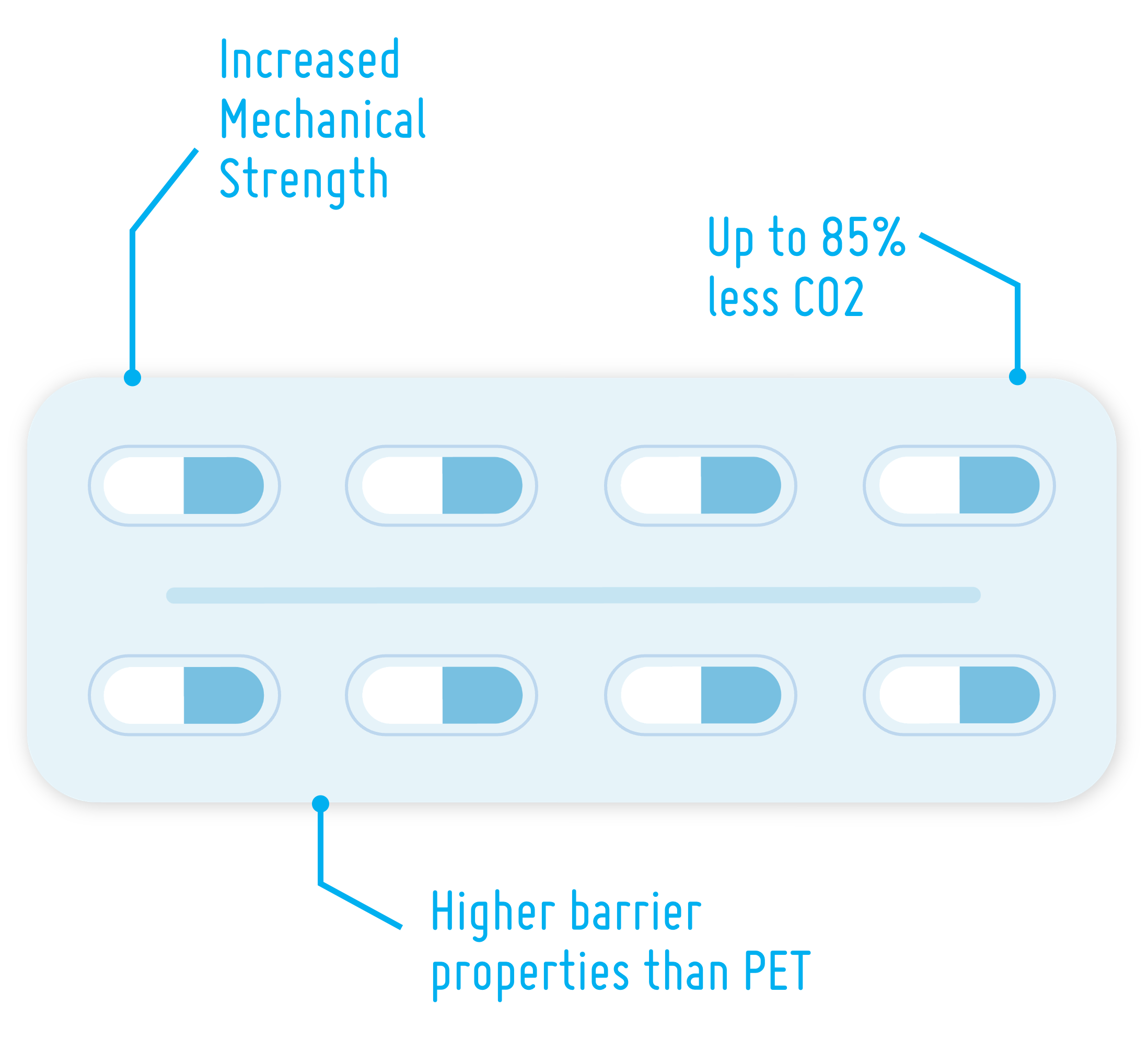

Maximum patient safety and the demand for environmentally friendly, recyclable solutions are putting pressure on the pharmaceutical industry. In this article, we take a look at PLA – a bio-based polymer – and its suitability as a future-proof material solution for drug delivery devices.